This is an old photograph of the cottage taken when I found it almost 25 years ago. It shows the horizon line of the field and sky behind the cottage before thousands of trees were planted for the pheasant shoot.

This is an old photograph of the cottage taken when I found it almost 25 years ago. It shows the horizon line of the field and sky behind the cottage before thousands of trees were planted for the pheasant shoot.

Almost a quarter of a century ago, I searched for a country cottage and found this one surrounded by pasture fields and big skies. Like many people, I knew pheasants were shot, but did not know about the logistics, practice, history or law of shooting, so it never occurred to me that one day my home could be, or would be, surrounded by people with guns killing pheasants.

The cottage was renovated and extended, and the small plot of land between the fields gradually became a garden.

When I designed the garden and spent peaceful years planting it, I never knew that one day there would a large enclosure erected at the bottom of it, to be filled each July with hundreds of pheasants. Nor did I know that people would stand either side of the garden to fire at pheasants which would fall dead on the lawn and in the flower beds.

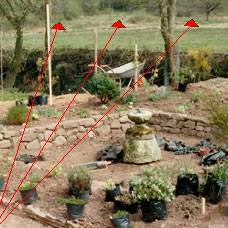

BEFORE - sowing grass seed and making the garden.

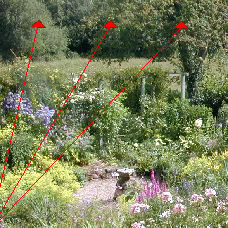

NOW - established lawns and flower beds.

Some of the future, unknown, shooting positions round my garden and home.

A netted enclosure for hundreds of pheasants was put just behind the trees.

About ten years after I bought the cottage, the landowner, who had recently taken to walking past on the lane, paused and told me he was going to turn some of his land into a shoot. "Good morning Sue. Just thought I'd let you know, we're thinking of turning some of our land into a shoot. Nothing to worry about. It won't make any difference to you – just a handful of us only four or five days in a year," with the added throw-away remark, "Oh, and I'll be planting lots of trees." I took him at his word – I like trees, and got on with my life.

The first sign of change was to the pasture fields that surrounded the cottage. A tractor came with posts, rolls of wire fencing and barbed wire. It had something on its end which banged the posts into the ground. Fences enclosed and divided the fields. That was followed by silent tree planting: thousands of 'sticks with roots', from bundles and bags, were slipped into the ground.

As the years passed, the fences turned into hedges, and rank weeds into scrub, and the scrub into trees.

The initial commotion of erecting fences and gates, then planting, had been disturbing, but I assumed once done, apart from the days of shooting, life would be quiet and private as before. There were not many pheasants when they appeared in the autumn; they were handsome and brought the dying year to life for a while, and by February they had gone.

But, as the years passed, the number of shooting days grew. So the number of pheasants, the size of the pens, and the volume of passing tractors, quad bikes, trailers and people grew too. Poles, netting, gates, hoses, corrugated iron, plastic barrels and feed, passed and re-passed my windows.

As the next decade passed, the coming and going to maintain the shoot became almost daily. Its proximity meant that days of enjoying privacy inside the cottage or outside in the garden were over. Some days were so intrusive I felt as if I was living in a goldfish bowl. Added to this was loss of sunlight. In the intervening years, the thousands of planted trees had grown, some very fast, along with the indigenous trees and hedges.

The cottage was thrown into pools of oppressive shade, the sunlight that used to dance on the fields and spill through windows was hampered by outstretched branches, the light filtering through the canopy of leaves was green.

I asked for one particular very close, older and large, self-sown ash tree to be felled. It shaded the south side of the cottage and frightened me on windy winter nights. But despite reassuring words it remained.

The incursion of the shoot had destroyed the way of life I had previously enjoyed and had anticipated enjoying in the future. Broken and beaten, I gave up in despair and decided to move. In all those years I never saw a pheasant being shot. One of my dogs was terrified of gunshot. Each day there was a shoot, across all the years, we piled into the car and stayed away from our home until the shooting was over.

So, twenty years after finding my home, which had been invested with much love and time, I had to search for another. I did find somewhere, but the purchase fell through just before exchanging contracts. It was now autumn, a few weeks before the beginning of another year's shooting.

Packed boxes were unpacked. The shooting season began. But we did not go out as we had done for so many years, as my dog, now old, was deaf. He couldn't hear the guns anymore or not acutely enough to bother him, so I saw people aim and fire at pheasants for the first time in my life.

They did not shoot in the far fields and trees, but beneath an upstairs window. It was horrifying. Their proximity to the cottage struck me more forcibly than the dying birds, and prompted my taking this picture to counter my incredulity.

Thereafter I photographed the people who surrounded my home with their guns and dogs, from my garden and through my cottage windows. Ten days later the lower branches of the large ash tree beside the house were removed, fourteen months after my first request the previous year. The camera had become a witness and defender. Trees were felled the following spring and some sunlight was restored.

My previous despair was replaced by a new need. I wanted not only to defend and protect the cottage as a home but to stand up to and expose the imposition of the sport of shooting. Over the next two years I recorded how a shoot worked.

A cock pheasant silhouetted against the sky, a living target. A sight I did not see until ten years after the shooting started. It is flying over my home, a few seconds before being shot.

As I watched, photographed and filmed, I grew to know the ignoble callousness of killing pheasants for pleasure. I saw and learnt about the long silences between drives, the stirring wave of nature moving ahead of the people, the sound of 'cracking' plastic flags. I became familiar with the marauding out of the woods up beside the garden, with frightened pheasants flying low past the house and then back over again to the thunder of gunshot. I came to know the smell of cordite and the tinkling of falling lead pellets, alternating with the thudding sound of bodies as they hit the ground … and with the silent floating feathers.

As the pheasants, their wings outstretched, came over the top of the now tall poplars, I slowly pieced the jigsaw together. I made sense of the tree planting, the maize crops and the position of feeder barrels. I began to understand the role of the beaters, guns and pickers-up, an entourage of people with dogs, sticks and guns, their different attire and the unspoken deference. I watched bemused as people bent down after shooting, picking things up from the ground – cartridge cases, which made me question the ones I had found repeatedly in the garden after I came home with the dogs when the shoot was over. Knowing nothing about guns I had assumed they flew through the air.

The tall poplar trees planted on the southern side of the cottage, to make pheasants fly high in the sky.

Three of the dozen or so beaters with sticks, whistles, walkie-talkies, plastic flags and dogs who circle the house.

I often howled in the silence after they had all gone. I felt isolated, not by winter snow and ice, but by being surrounded by a group of people whose culture seemed to make them oblivious of the ugliness they wrought. They laughed and joked at my expense, with sarcastic remarks and pseudo-gentility.

Now the internet was at hand, it helped in a way that would have been impossible ten years earlier. It became apparent that what had been happening around my home had been a master plan. Its consequences had therefore been known before the first tree had even been planted: the stature of shadow-casting trees, the building of pens for hundreds of pheasants, the disturbing access for maintaining and feeding, and the standing beside my home for the shooting. I had known none of this, adjusting my tolerance with each incursion as it unfolded. What a naïve, gullible fool I had been.

The ugly and sinister pen constructed at the bottom of my garden, which is filled with hundreds of pheasants every year.

What baffled me was how anyone could contemplate designing a few hours of recreational activity predicated on snuffing out a person's sunlight, peace and privacy and trapping a home in the culture of killing for fun. To put trees on one side of a house, pheasants on the other, and stand in the middle to kill them, seemed beyond all human decency. What makes a group of people so evidently feel 'entitled' to behave in such a way and with such alacrity?

But the biggest thought of all was, "This can't be right. How can this be?" So I rang the police and learnt, indeed they could stand all round my home, right up to the boundary, and shoot. All anyone needs is a shotgun licence (actually you can borrow a gun too, and use it without experience)(1) and the permission of the landowner. I saw my MP, got sympathy but the same reply.

I read and read; the answer lies in our country's history, in land, vanity and power.

Every bone in my body says this is ugly, selfish, indecent and unjust. I felt bullied, intimidated and broken. I still do to a degree, not only by the people with their guns and dogs but by the laws of my country which foster such selfish tyranny. Because of the law, this could happen to any home, family and child living in the countryside. Hence this website and my appeal to our legislators.

Do we live in a country where common decency takes precedent over the sport of shooting, or one in which the sport of shooting outweighs common decency?

- Firearms Act 1968, s11(5) http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1968/27